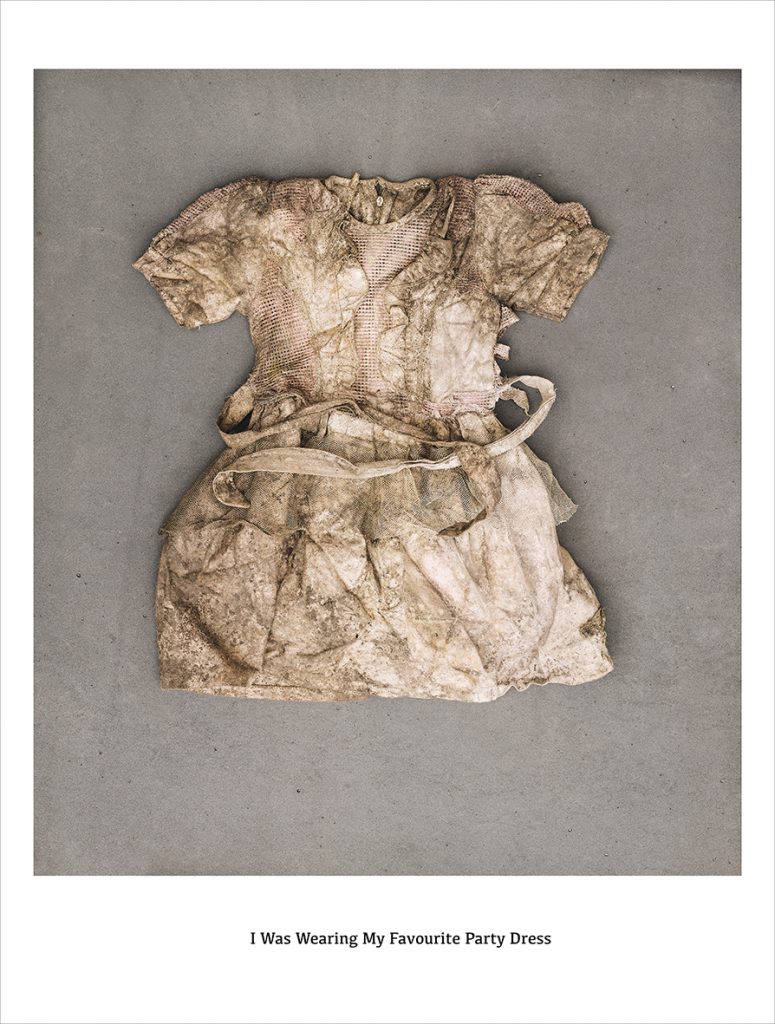

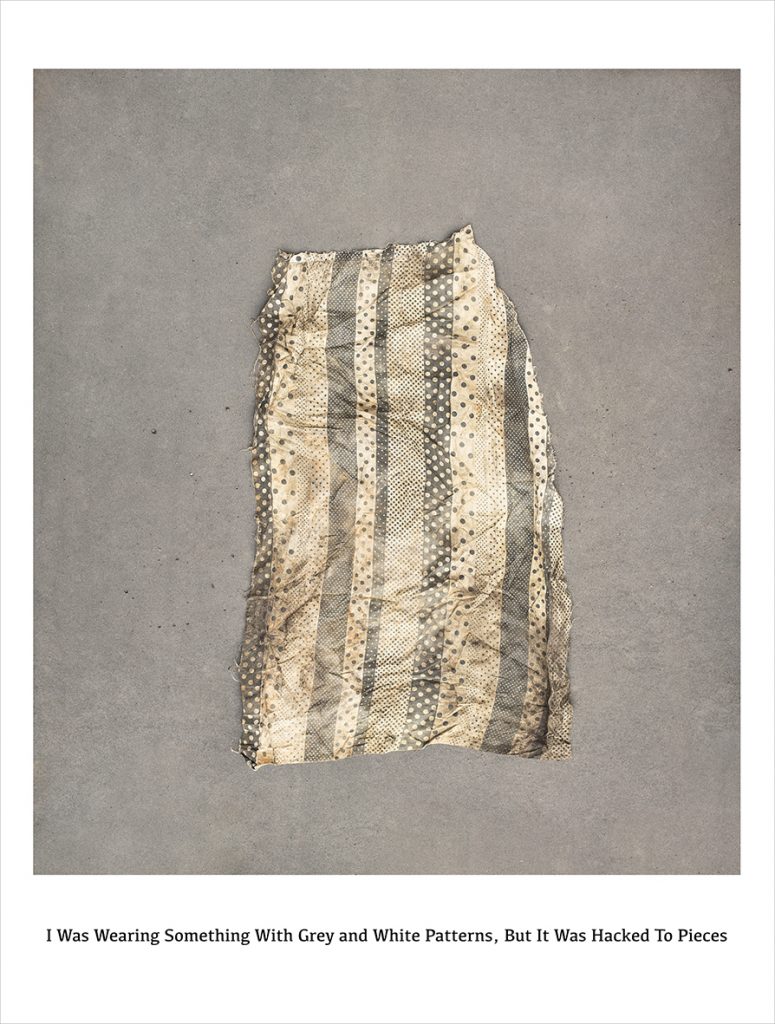

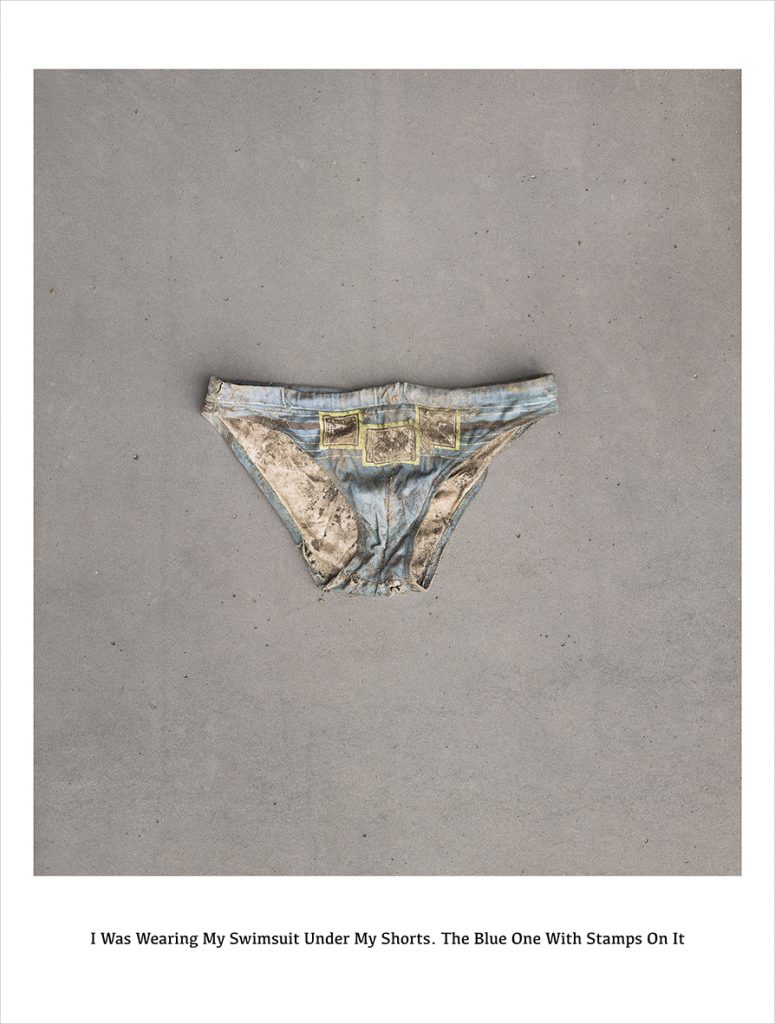

The Joy of Paris Photo : discovering a remarkable work. As you wandered in aisles of the fair, you are attracted by the number of photos that are installed, right next to the gallery Deepest Darkest (South Africa). Almost a hundred images made with the same setting : muddy clothes or pieces of clothes, laid flat on a grey background. The three walls of this room were all covered by the photos : from the top to the bottom. Once in the middle of this installation, you understood only by emotions what is going on here. At the bottom of these images : a text in the first person written in the past tense, embodying people who did not appear in these same images. Each of these garment came up from a mass grave dicovered in Rwanda in 2018. Each of these photos is a portrait of Rwanda genocide victims drawn by Barry Salzman, a South African photographer. We met Barry who gave us time to explain how humanity drives him through his art practice.

Your work « The Day I became Another Genocide Victim » is exhibited for the first time in Europe at Paris Photo. It strikes us by its very strong emotional feelings.

Barry Salzman : I started this work in 2018… I must have spent thousands of hours working on it, on editing, etc. That work is still so personal, so emotional… It always takes me back to the experience of handling those clothes, feeling them when they came out of the grave. Yesterday, here at the fair, a group from International Center of Photography (ICP – New York) came to ask me to talk. They were twenty people in the group. And I started to talk and I couldn’t stop crying. I feel it intensely all the time… and I that feeling… I’d never get used to it.

Does this mean that you carry this pain, these tears with you always?

I think that the fact that I talk about it all the time and I work on it is almost like part of the healing. I don’t think of it any longer as a traumatic event… I think of it as a deeply touching human experience. For me, when I cry, tears are not tears of trauma but tears of humanity.

Like the How we see the world (a century of genocide), your previous series on genocide places, this work is still linked to your personal story as being a descendant of holocaust victim… Can you talk more about this special link ?

It is how I came to this work… It is the reason I started on the subject matter. My mother’s family was directly impacted by the holocaust. When I was at art school, I did a project called It never rains on Rhodes. And it looked at my maternal heritage. And a big part of that had to do with people who perished in Auschwitz. When that work got viewed by critics and festivals, people said : ‘we know the story, we may not know that lady but we know the story’… and I got really upset because I thought then you destroyed my grand-mother’s sister… But after spending 100 hours with holocaust survivors, you realise that we will never know the story. And I decided I will never stop trying! I will dedicate my art practice to looking at different ways to examine that story… And I would say when everybody say to me ‘we know the story’, I will always say : ‘if we know the story so well, how can we justify repeating again and again and again and again’! But I didn’t want to work specifically on the holocaust… There are many talented artists, historians, and philosophers who have addressed that… What I became so interested in, is the recurrence and what is it about the way we look, that continues to enable and perpetrate genocides… I think so much of the responsibility lies with us. And so the holocaust experience, my family experience’s got me started on this. I became much more interested in the general fragility of humanity and not specifically the holocaust.

Why did you choose photography to express your feelings ?

I say sometimes jokingly, but I don’t think it’s really a joke… I think I have such creative ideas and concept, but I don’t have the ability to work with my hands on drawing, on painting, on sculpture… The mechanic of the camera became the tools for selfexpression for me… if you look at the core part of my practice… my landscape works… Everybody says that they feel paintily. They look like paintings… And I use the camera when I’m working in ways that the camera was never designed to work… I move it a lot, I do slow shutter speed, I introduce blur… All because, I think in my heart, I am really a frustrated painter!

That’s why you came into photography ?

My very early entry into photography had a lot to do with humanity and activism… Because, I first got a camera when I was a young teenager and I was at school in South Africa. I remember my first experiences with the camera, were using it to explore apartheid in my country. That I would go into areas, at the time, only black people were allowed to go… I’d go in with my bicycle and my camera to meet the people who lived there and try, through the lense of the camera, to understand this enormous inequality that was apartheid. So, I think from the very beginning, the camera has always been a voice of activism for me.

So, your practice has always been about work challenging difficult issues around humanity ?

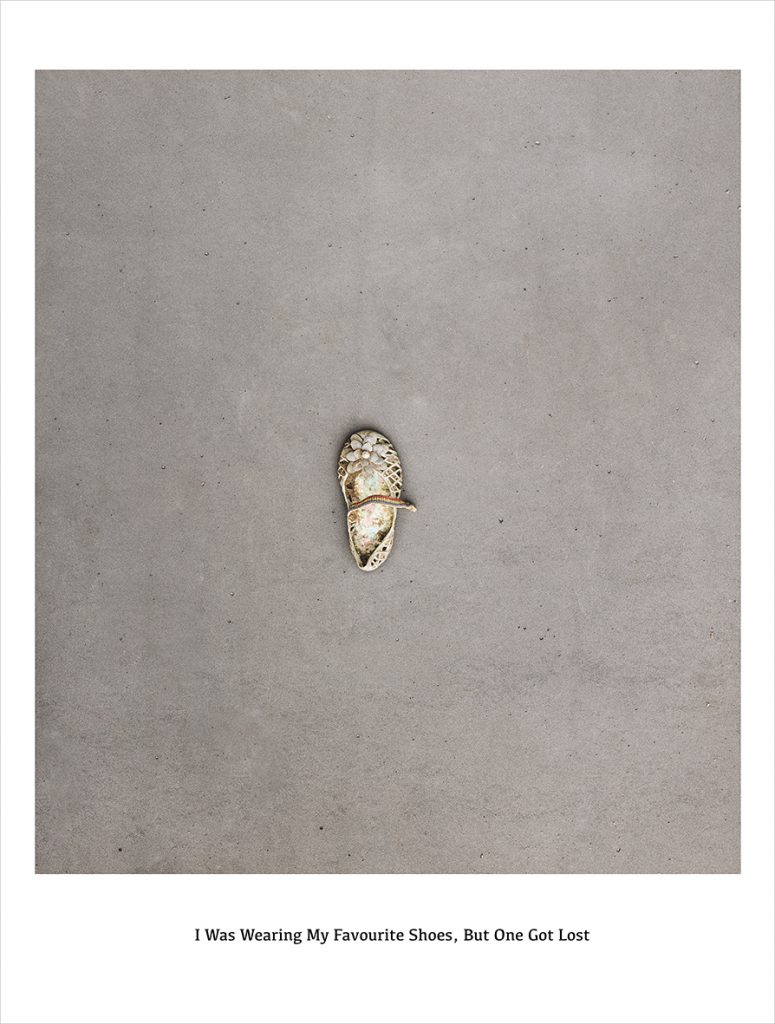

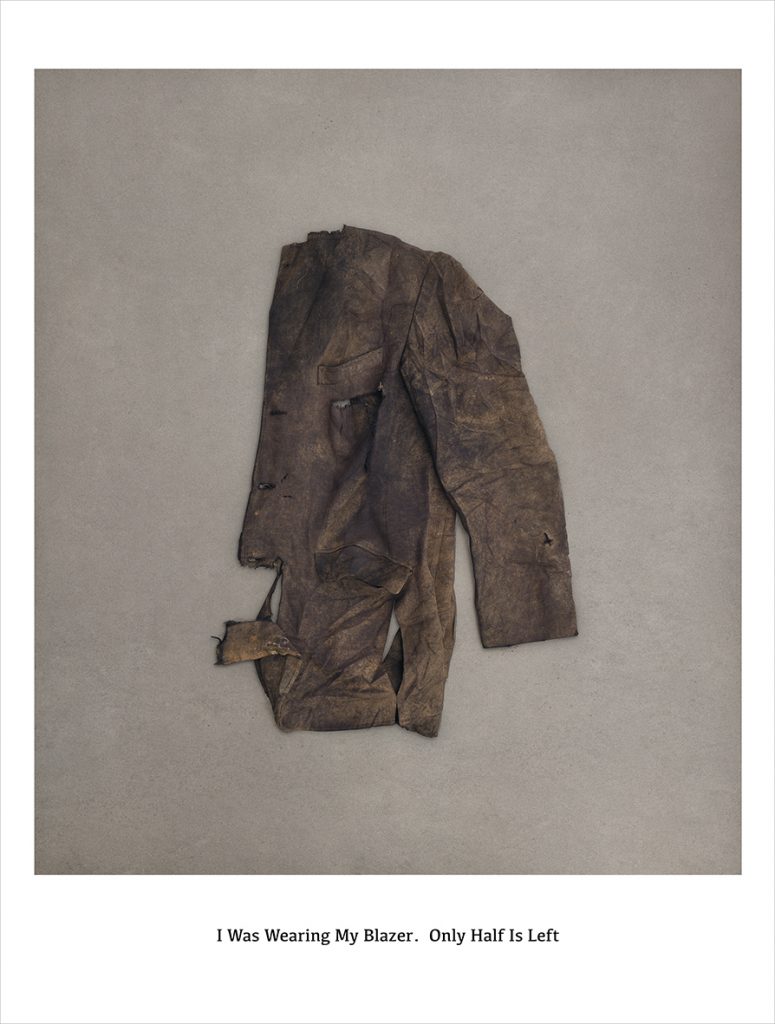

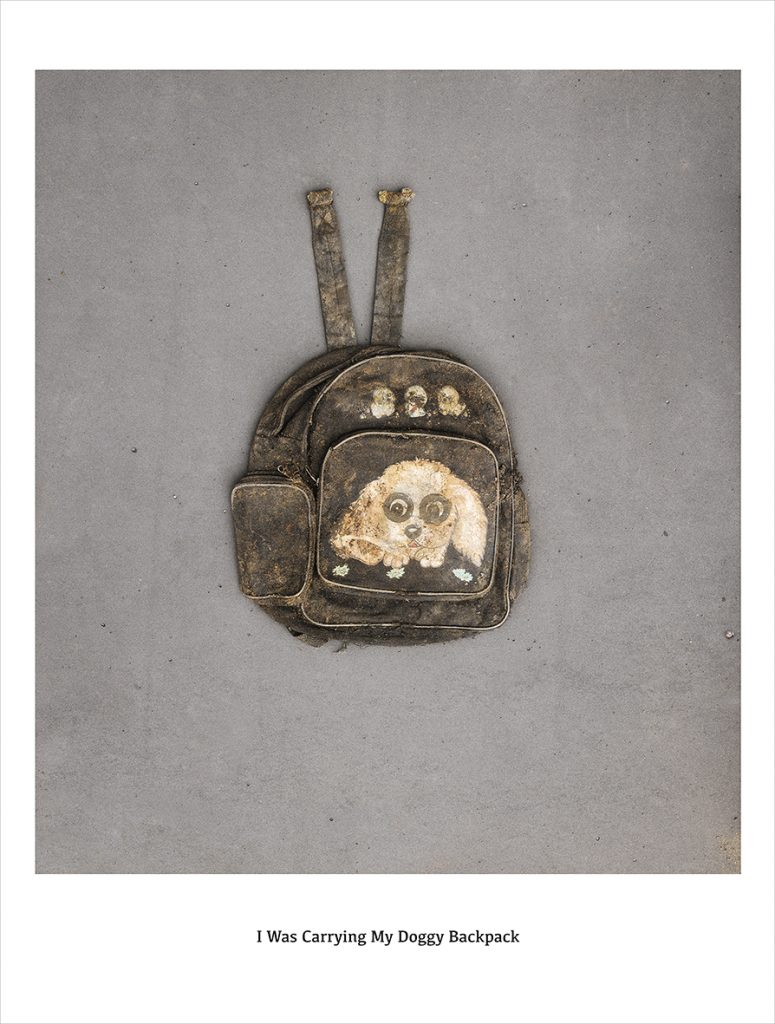

Yes ! For this specific project, The Day I Became Another Genocide Victim was never a work I intended to exhibit… Purely, I tried to understand what happened on than same land in Rwanda nearly 25 years ago before. I didn’t take my camera the first time I went to the sight. I left it in the car. I just said to the people I was working with ‘I want to go to understand what happened here’, in the same way when I worked in Poland… I went to Auschwitz… I didn’t take pictures first. I went there as an artist. I wanted, as much as I could, to feel the emotion of the place… That day, they just discovered the mass grave… They just started to dig and the clothes were coming out of the ground with skulls, mud. I left after half an hour, or twenty minutes. A few days later, I felt so bad that I left… I was thinking, those people died in the most inhuman death possible… You know, genocide victims died in the most inhumane way where they are not even recognized as people anymore. And I saw these clothes coming out, being piled up and I started feeling in the days afterwards that it was almost compounding the dehumanisation. And I felt like I had to do something. And I want to recognize each one as a person. Because the piles of clothes were so big and so anonymous but each one is a person with a all life story : a mother, a father, a brother, a sister, friends, teachers… And I think, by handling each one, and trying to clean it off, I started to understand the individual behind the mass atrocities. And I think that when you are involved in mass atrocity, you focus on the magnitude and the individual becomes anonymous. And what I wanted to do with that was to help myself to understand that behind one million dead people in Rwanda, there are one million individuals with a life story. And that work was so helpful for me to start to personalize the story of genocide. Because genocide by definition has nothing to do with individuals… You are not killed because you are Nadia and someone doesn’t like you, but because you belong to an ethnic group that they try to eliminate…. The definition of it is inhuman!

That’s why you consider each of these images as portraits and not as still lifes?

For me, these are portraits… When I was shooting this little white dress, I could see the girl. If you can see her, you know her. You can imagine her friends, her birthday party where she wore a pretty dress. Yes, for me very much… When I put the text… I never worked with text. It’s not part of my practice… But it was so clear to me that I had to put a text in the first person.

How did you get the idea to add a text ?

I didn’t think about it. But it was clear to me that the little boy carrying his doggy backpack, was a little boy carrying his doggy backpack… It just came so intuitively to me. Some people say : ‘you don’t need the text, it’s too didactic… we can see it’s a doggy back pack’… but I say ‘I need the text’… because, for me it completes the first person narrative. This is an individual. So I felt very strongly about including the text.

If you did not intend to exhibit this specific work, did you plan to do something else with, like a book or something else even ?

First, I wanted to keep it for me… to fuel me to do my landscape work at places of genocides. Because it keeps reminding me that behind each one of these landscapes, there is a human being with a story.

But in February this year, the director and curator of the Cape Town Art fair, Laura Vicenti who knows me and my work well, said “Trust me Barry, this work needs to be seen in an art fair. Because art fairs can become so frivolous… it’s all about the social, and the cocktail party… we need to be reminded of the gravitas, the meaning of it ». Then, she put me right at the front door. It was the first thing that people saw ! The reaction was so unbelievable. It was on the heels of that, that we submited the project for Paris Photo and here we are ! for the first time in Europe… Before, it has been shown in Cape Town, Holocaust & Genocide Museum in Johannesburg this year for the “full 100 days” of the genocide in Rwanda. So they had it up to commemorate the 28th anniversary for the 100 days. And I was invited there to be the keynote speaker… Now, what we really try to do is to find an institution or a museum that can create a large public audience for it… So I am hoping that we can place it within a institution, a foundation… Even I would love love love to show it at the Arles festival. The most important thing for me is to get seen, that it has an audience and that it touches people and that it reminds people. We have the war in Ukraine going on, now… Those numbers become meaningless to us as civilians deaths. And we have to remember, it is each of us as a person.

You could do the same work in 25 years in Ukraine… you will get the same images!

Yes, I think that’s the point… the point of my landscape works is to address this notion of the recurrence. Particularly, what is it about our role as public witness that enables the recurrence of these dark moments in history. That’s what my landscape works talked about, that’s the core part of my artistic practise.

Do you work with Rwanda authorities ?

I worked very closely when I was shooting that… I did offer to the Kigali Genocide Memorial the work as a gift. They have chosen so far (I hope they’ve changed their mind) not to take it. I guess because the clothing text has a very special meaning in Rwanda because the bodies and the people were so badly mutilated… That clothing became the way many people identified whether their families had been killed. So there is a very personal connection… too confronting for Rwandan people. What they do, they leave the clothes on public display for a few months and then they take them to central memorial sites. They do that in the hope that maybe someone will be able to identify the clothes. Just after the genocide, many people were able to identify the clothing of their family members or friends.

As you are so involved in this work that you are almost like a messenger…

Oh that’s a great way to describe it. Because of this work, I said to people that the landscape work is my work, is my idea, is my concept, is my aesthetic… no one else has done the same thing ! The way I tried creating filters between evidence and witness by moving the camera is all mine. I own it. Rather than with that work, I feel, it’s not my work… I feel the custodian of those stories. You can see : aesthetically, it’s completely different. People can’t believe that these two different works come from the same person, so I sort feel like I am the care taker of those stories. And I would like to pass that duty of responsibility on to a bigger institution that has a bigger audience. When we start to hear this increasing hate speech today, and people don’t take it seriously, I think to myself, that’s the beginning… every genocide starts with that. The United Nations, I have been working with them a little on this project, are introducing this year an International day of Hate speech to try to raise the profile of how damaging and dangerous hate speech is if it goes unchecked. And I think that Rwanda tells us that story in the most frightening way. So I said, as a human, to people that Rwanda is my story, it’s your story. And we have all a duty to understand it and to talk about it and never to forget what happened in Rwanda. I feel in some strange way almost more, even if my family connections was to the holocaust, my emotional connection to the work is through Rwanda.

This interview was lead the 11th of November at Paris Photo.

Gallery Deepest Darkest – Cape Town, South AfricaInternational Day for Countering Hate Speech, 18 June 2022

The French version of this interview is here.